开始给十年级中文班讲“汉字六书”,也就是汉字造字法。我觉得,汉字虽然数目繁多,看起来也复杂难记,但只要了解其基本造字规律,就能掌握和认识更多汉字。因此,在十年级学生毕业离开中文学校之前,希望他们能有这方面是知识。本学年,十年级学生也将做相关课题作业。下面是有关“汉字造字法”的内容。

汉字六书(造字法)

Formation of Characters

-

Main articles: Chinese character classification and radical (Chinese character)

The early stages of the development of Chinese characters were dominated by pictograms, in which meaning was expressed directly by the shapes. The development of the script, both to cover words for abstract concepts and to increase the efficiency of writing, has led to the introduction of numerous non-pictographic characters.

The various types of character were first classified c. 100 CE by the Chinese linguist Xu Shen, whose etymological dictionary Shuowen Jiezi (說文解字/说文解字) divides the script into six categories, the liùshū’ (六書/六书). While the categories and classification are occasionally problematic and arguably fail to reflect the complete nature of the Chinese writing system, the system has been perpetuated by its long history and pervasive use.[6]

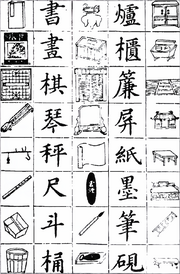

1. Pictograms (象形字 xiàngxíngzì)

Contrary to popular belief, pictograms make up only a small portion of Chinese characters. While characters in this class derive from pictures, they have been standardized, simplified, and stylised to make them easier to write, and their derivation is therefore not always obvious. Examples include 日 (rì) for “sun”, 月 (yuè) for “moon”, and 木 (mù) for “tree”.

There is no concrete number for the proportion of modern characters that are pictographic in nature; however, Xu Shen (c. 100 CE) estimated that 4% of characters fell into this category.

2. Ideograph (指事字, zhǐshìzì)

Also called a simple indicative, simple ideograph, or ideogram, characters of this sort either add indicators to pictographs to make new meanings, or illustrate abstract concepts directly. For instance, while 刀 (dāo) is a pictogram for “knife”, placing an indicator in the knife makes 刃 (rèn), an ideogram for “blade”. Other common examples are 上 (shàng) for “up” and 下 (xià) for “down”. This category is small, as most concepts can be represented by characters in other categories.

3. Logical aggregrates (會意字/会意字, Huìyìzì)

Also translated as associative compounds, characters of this sort combine pictograms to symbolize an abstract concept. For instance, 木 (mu) is a pictogram of a tree, and putting two 木 together makes 林 (lin), meaning forest. Combining 日 (rì) sun and 月 (yuè) moon makes 明 (míng) bright, which is traditionally interpreted as symbolizing the combination of sun and moon as the natural sources of light.

Xu Shen estimated that 13% of characters fall into this category.

4. Pictophonetic compounds (形聲字/形声字, Xíngshēngzì)[1][2]

Also called semantic-phonetic compounds, or phono-semantic compounds, this category represents the largest group of characters in modern Chinese. Characters of this sort are composed of two parts: a pictograph, which suggests the general meaning of the character, and a phonetic part, which is derived from a character pronounced in the same way as the word the new character represents.

Examples are 河 (hé) river, 湖 (hú) lake, 流 (liú) stream, 沖 (chōng) riptide, 滑 (huá) slippery. All these characters have on the left a radical of three dots, which is a simplified pictograph for a water drop, indicating that the character has a semantic connection with water; the right-hand side in each case is a phonetic indicator. For example, in the case of 沖 (chōng), the phonetic indicator is 中 (zhōng), which by itself means middle. In this case it can be seen that the pronunciation of the character has diverged from that of its phonetic indicator; this process means that the composition of such characters can sometimes seem arbitrary today. Further, the choice of radicals may also seem arbitrary in some cases; for example, the radical of 貓 (māo) cat is 豸 (zhì), originally a pictograph for worms, but in characters of this sort indicating an animal of any sort.

Xu Shen (c. 100 CE) placed approximately 82% of characters into this category, while in the Kangxi Dictionary (1716 CE) the number is closer to 90%, due to the extremely productive use of this technique to extend the Chinese vocabulary.

5. Associate Transformation (轉注字/转注字, Zhuǎnzhùzì)

Characters in this category originally represented the same meaning but have bifurcated through orthographic and often semantic drift. For instance, 考 (kǎo) to verify and 老 (lǎo) old were once the same character, meaning “elderly person”, but detached into two separate words. Characters of this category are rare, so in modern systems this group is often omitted or combined with others.

6. Borrowing (假借字, Jiǎjièzì)

Also called phonetic loan characters, this category covers cases where an existing character is used to represent an unrelated word with similar pronunciation; sometimes the old meaning is then lost completely, as with characters such as 自 (zì), which has lost its original meaning of nose completely and exclusively means oneself, or 萬 (wan), which originally meant spider but is now used only in the sense of ten thousand.

This technique has become uncommon, since there is considerable resistance to changing the meaning of existing characters. However, it has been used in the development of written forms of dialects, notably Cantonese and Taiwanese in Hong Kong and Taiwan, due to the amount of dialectal vocabulary which historically has had no written form and thus lacks characters of its own.